Author: Sara Benedi Lahuerta and Ania Zbyszewska

Download Full Paper (PDF) ›

Download Brief (PDF) ›

Summary

The EU equality law framework is often critiqued for its lack of internal and external coherence, which are a legacy of its gradual and piecemeal development. The, at times, poor articulation of EU equality law with other areas of social and economic policy also necessary to achieving substantive equality objectives in practice is similarly critiqued, but less often invoked in equality law debates. Taking such a broader notion of equality law as a starting point, we suggest new possibilities for developing and equality-related legal and policy framework at the EU level that is more congruent, better articulated, and, hence, more likely to facilitate equality goals.

Drawing on our research, we focus on three specific examples to illustrate how such overall coherence can be achieved within EU equality law and policy:

- explicit protection for gender identity discrimination

- accommodation of workers’ diverse needs at the workplace, and

- relationship between working time, work-family reconciliation and gender equality

Introduction

The development of equality legislation at the European Union (EU) level is one of the major achievements of the European integration project, and its role in driving advances in equality law and policy in many EU member states is undeniable. Yet, the currently enacted EU equality law framework is not without shortcomings. Its variegated character and lack of coherence are often cited as particularly problematic, both from a normative perspective as well as for equality law’s future development.

The internal incoherence of this framework is exemplified by the existence of a ‘hierarchy of rights’, wherein protections for certain grounds on the basis of which discrimination is prohibited are more robust than for others. Gaps in the material scope of the equality directives (e.g. the fact that discrimination in the access to goods and services is only covered for racial and sex discrimination) undermine substantive protection against discrimination, and some gaps in coverage render potential non-discrimination grounds (e.g. gender identity) almost entirely out of the scope of formal protection.

Crucially, the misalignment between the EU equality legal framework and international approaches to equality also contributes to external incoherence. EU equality law lags behind some recent developments in international equality law conventions and recommendations, and, in some instances, it may not be fully in line with the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

Another form of incoherence stems from occasional misalignment between formal EU equality law and other legal and policy fields that fall outside of the former’s jurisdictional boundaries but which are essential to achieving equality objectives in practice (working-time regulation, as we explain here, is one such field). While less often invoked in equality law debates, this broader systemic incoherence also poses a significant problem from the perspective of substantive equality.

Rather than being normatively based, the inconsistencies resulting from the patchy nature of the EU equality law stem from the piecemeal manner in which it developed over time. This development, in turn, has depended on a range of structural and political factors, which have shaped the EU’s legal competences and institutional architecture, including the pool of actors capable of influencing decisions on particular legal and policy developments. Similarly, historical particularities and contingencies of policymaking, rather than purely normative grounds, have contributed to the manner in which the EU equality law framework articulates, at times uneasily and incompletely, with other EU legal and policy fields that do not necessarily fall within equality law ‘proper’, yet which are essential to achieving equality objectives.

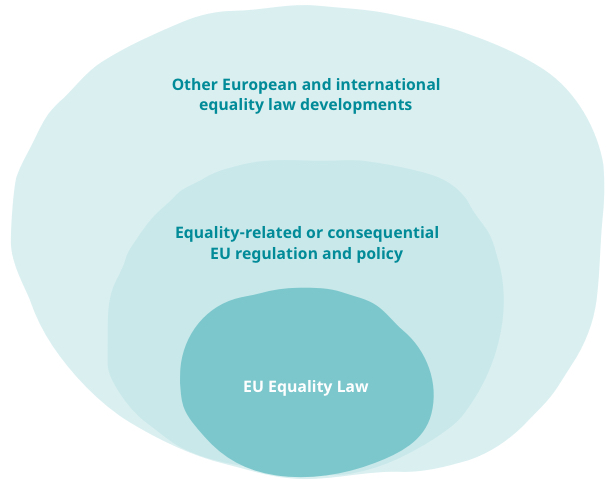

Addressing these various forms of incoherence is essential to developing and improving the EU equality framework. In this research-based policy paper, we suggest that embracing a broader notion of equality law – one, which is attentive to both internal and external coherence, and the dynamic interactions between equality law and related policy fields – opens possibilities for developing an equality-related framework at the EU level that is more congruent and better articulated (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Equality Law: Internal, Systemic, External Coherence

Internal, systemic and external coherence of EU equality law can be improved in various ways. Here, we wish to illustrate some examples of how more coherence could be achieved by drawing on three specific case studies derived from our previous research. Specifically, we focus on: 1) better protection of gender identity discrimination, 2) accommodation of workers’ diversity at the workplace (particularly, but not only, as regards religious diversity), and 3) better alignment of working time, work-family reconciliation and gender equality measures. While the first two refer more explicitly to the internal and external cohesion of equality law, the last embraces a wider, systemic conception of equality law in the EU context that is attentive also to policy fields that are consequential for equality, even if they are not positioned within equality law as it is traditionally understood.

Of course, these case studies are only illustrative. We are not suggesting that implementing the policy recommendations we make in relation to each of them would be sufficient to improve the coherence of the EU equality framework as a whole, even if, as we maintain, it would go some way towards that goal. What these examples do demonstrate, however, is that thinking of equality law in a way that is attuned to both its internal and external dimensions, and its nesting in a wider policy context is necessary if we are to facilitate achieving the equality goals in practice.

We conclude with broader recommendations for future development of EU equality law. Namely, we argue that while human dignity and substantive equality should be the key principles guiding the revision and amendment of the current equality law and policy framework in the coming years, such a framework is necessary also to uphold and enable the achievement of a range of interrelated policy objectives, including the long-term sustainability of the European integration project.

Exploring the Alternatives

Better recognition of Gender Identity as a

Non-discrimination Ground

Since the ECJ ruling in P v S (Case C-13/94) in 1996, ‘sex’ discrimination has been interpreted as including gender reassignment discrimination. More recently, Recital 3 of the Recast Directive (2005/54/EC) established that ‘the principle of equal treatment for men and women […] also applies to discrimination arising from the gender reassignment of a person’. However, EU law does not prohibit discrimination on the basis of gender identity. This entails three problems.

1// Only few Member States have expressly prohibited gender reassignment discrimination in employment. The lack of an express prohibition of gender identity discrimination may have some bearing on the fact that 41% of respondents to an EU survey were not aware of laws prohibiting gender identity discrimination in employment, whereas the rate was lower for sexual orientation discrimination, which is explicitly outlawed at the EU level. It may also partly explain why, among LGTB people, transgender people are the ones who suffer higher levels of discrimination, both in access to employment (30%) and in employment (23%).

2// The interpretative solution derived from P v S is not entirely satisfactory because gender reassignment is only one particular aspect of gender identity and gender expression. The term ‘trans’ is generally used to refer to people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from the sex assigned to them at birth, which includes people who live in their desired gender on a continuous basis without undergoing gender reassignment medical treatment and/or surgery, as well as people who occasionally cross-dress. Furthermore, many trans people do not understand gender in binary terms: they may see themselves as ‘more than male and more than female’, or as neither male nor female.

3// The real scope of the CJEU interpretation in P v S and subsequent cases is unclear. Does it only apply to gender reassignment or can it also apply more broadly to gender identity discrimination? Within the academic literature there is disagreement (see ‘Key reading’, Benedi Lahuerta 2016). The best way to address this uncertainty and to achieve external coherence with the growing international accord would be to expressly prohibit gender identity discrimination in legislation.

To address these problems and improve internal coherence (avoid a hierarchy of discrimination rights) and external coherence (international conventions and recommendations), two options could be considered:

First, explicitly prohibiting gender identity discrimination in binding legislation, including both new legislation (i.e. the proposal for a new Horizontal Directive on discrimination in access to good and services, COM(2008)0426) and future amendments/recasts to existing legislation (EU Parliament 2014). For this purpose, the term ‘sex’ in article 19 TFEU could be stretched to include ‘gender identity’ (see below), or alternatively, article 352 TFEU could be used as a legal basis. This provision was used in the past to enact sex equality legislation (e.g. Directive 76/207/EEC) when there was not a specific legal basis, but its use could be more controversial nowadays, given the existence of a more specific legal basis (article 19 TFEU).

Secondly, the Commission could issue guidelines specifying that the term “sex” in article 19 TFEU and all equality directives should be interpreted as including ‘gender identity’ (EU Parliament 2014). Indeed, discriminatory conduct against trans people is always based on the fact that their preferred gender identity differs from the sex that they were physically given at birth. This was implicitly recognized by the CJEU in P v S, where it was stated that gender reassignment discrimination ‘is based, essentially if not exclusively, on the sex of the person concerned’. This progressive interpretation would also be supported by the increasing acceptance of different expressions of gender identity by EU society (Eurobarometer 2015), which, relying on the Canadian doctrine of ‘living tree’ (Sheppard 2001; Miller 2009), would support a dynamic reading of the equality directives, in line with societal changes.

Key Policy Recommendations

- Amend the equality directives to include gender identity as an additional ground, and include gender identity in the Horizontal Directive Proposal (COM(2008)0426) and in any amendment/recast to existing legislation (preferred option).

- Amend all the equality directives to clarify that any reference to sex discrimination includes gender identity discrimination (alternative option).

- Issue guidelines specifying that the term “sex” in article 19 TFEU and all equality directives should be interpreted as including ‘gender identity’ (alternative option).

Supplementary policy recommendations

- Better monitoring the implementation at national level of the equality directives that already include gender reassignment discrimination within their scope (particularly, Directive 2006/54/EC).

- Strengthening efforts to encourage improvements at national level on the EU Commission List of Actions to Advance LGTBI equality, particularly as regards mainstreaming of gender identity protection, training equality bodies and other legal enforcement professionals on gender identity discrimination law, and raising general awareness on gender identity discrimination and relevant legislation and case law.

Accommodation of workers’ diverse needs

EU equality law contains several provisions that require the accommodation of working environments to certain workers’ circumstances. The more widely known accommodation requirement concerns the duty to take appropriate measures to enable disabled persons to have access and full participation in employment, provided this does not impose a ‘disproportionate burden on the employer’ (Directive 2000/78/EC, article 5). However, this is not the only example. There is also an EU law duty to accommodate working conditions for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, if the normal working conditions would entail risks for their health and safety (Directive 92/85/EEC, article 5(1)). Workers returning from parental leave have also the right to request changes to their working hours and/or patterns (Directive 2010/18/EU, clause 6(1)). The recent Commission proposal for a new Work-Life Balance Directive also includes a ‘right to request flexible working arrangements for caring purposes’ (COM/2017/0253 final, article 9). This highlights that accommodating working environments to workers’ circumstances can be relevant in many different contexts, and suggests that EU equality law should be flexible enough to facilitate workplace adjustments to an increasingly diverse workforce. In fact, in some jurisdictions, accommodation duties also apply to gender, national origin, age (Canada) and religion (US, Canada). Considering that religion is the ground for which discrimination is seen as having rised more since 2012 (Eurobarometer 2015), the increasing racialization of Islam in Europe (Garner and Selod 2015; Müller-Uri and Opratko 2016) and the salience of recent CJEU case law in this field, this case study puts more emphasis on the accommodation of religious needs at the workplace. However, many normative considerations could be relevant to other grounds.

Extending and/or reinforcing the possibilities to accommodate diversity at the workplace beyond its current boundaries would improve the internal coherence of EU equality law. Arguably, it would also improve external coherence because ECtHR case law on indirect discrimination in private employment suggests that employers should ‘treat differently persons whose situations are significantly different’, where possible, unless there are objective and reasonable justifications not to do so (Thlimmenos v Greece, App. No. 42393/98; Eweida v UK, App. No. 48420/10).

While one possibility would be extending the duty of reasonable accommodation to religion or belief (and other relevant grounds) through legislative action, this could be very controversial and even politically unachievable. Therefore, a more realistic option could be considering that the concept of indirect discrimination requires the reasonable accommodation of employees’ needs, stemming from circumstances such as their religious faith, their gender identity or their age, unless the employers’ reasons not to do so are justified, i.e. they pursue a legitimate aim and are proportionate.

In the field of religion, in the 1970s, the ECJ already recognised in Prais (Case 130/75) that the accommodation of religious beliefs was ‘desirable’. The recent CJEU judgment in Achbita (Case C-157/15) seems to point in that direction in that it implies that the EU concept of indirect discrimination requires ‘tak[ing] into account the interests involved in the case and to limit the restrictions on the freedoms concerned to what is strictly necessary’. However, the CJEU only discussed the need to balance interests at stake in passing, and it remarked that the accommodation of manifestations of religious beliefs should not impose ‘additional burdens’ on the employer and it should take into account the employer’s ‘inherent constraints’. Therefore, this ruling has some limitations: 1) it does not provide detailed guidelines on how to balance the ‘interests’ at stake; 2) it does not make a distinction between public and private employers, an aspect which tends to be relevant in the ECtHR case law; 3) it seems to put more emphasis on the interests of the employer than on those of the employee.

Policy Recommendations

- Promote a better understanding of the EU concept of ‘indirect discrimination’ and how it can be used at national level to accommodate relevant employee rights at the workplace.

- Encourage discussion at EU and national level on how to develop balanced approaches to the accommodation of diverse workers’ needs at the workplace.

- At the next occasion, the CJEU should provide more detailed guidelines on how to balance employer/employee rights and interests in these cases.

Working Time, Work-Family Reconciliation and Gender Equality

There is widespread agreement that ‘family friendly’ policies that recognize gendered dynamics and patterns of care provision, yet which facilitate the possibility of more equal sharing of unpaid care work between men and women, tend to support work-life balance and women’s employment in the most egalitarian manner (Fagan et al 2012; European Commission 2017; see ‘Further reading’ Zbyszewska 2016). While the biological (sex) difference necessitates special accommodation of pregnancy, there is no reason for other ‘family friendly’ instruments or rights to be directed at women only. Instead, work-family reconciliation policies should encourage and enable redistribution of unpaid care work between parents or partners by, for example, extending rights to care leaves and to remuneration while on leave also to men (Kresal and Zbyszewska 2017).

There is widespread agreement that ‘family friendly’ policies that recognize gendered dynamics and patterns of care provision, yet which facilitate the possibility of more equal sharing of unpaid care work between men and women, tend to support work-life balance and women’s employment in the most egalitarian manner (Fagan et al 2012; European Commission 2017; see ‘Further reading’ Zbyszewska 2016). While the biological (sex) difference necessitates special accommodation of pregnancy, there is no reason for other ‘family friendly’ instruments or rights to be directed at women only. Instead, work-family reconciliation policies should encourage and enable redistribution of unpaid care work between parents or partners by, for example, extending rights to care leaves and to remuneration while on leave also to men (Kresal and Zbyszewska 2017).

This sort of approach has been for some time championed at the EU level, and is integral to the European Commission’s 2015 ‘New Start’ initiative and the recently proposed Directive on work-life balance for parents and carers (COM/2017/0253 final).

As the ‘New Start’ initiative reflects, leave rights are only one component of what is required for a family friendly workplace, and the initiative emphasizes a ‘comprehensive’ approach that encompasses a range of ‘mutually reinforcing measures’, both legislative and non-legislative, including, inter alia, flexible work arrangements, child care and long-term care, and tax measures.

In so far as the day-to-day balancing of work and family duties is concerned, working hours and patterns or access to care services are far more significant than leave policies. While flexibility in arranging work tends to be emphasized as crucial for work-family reconciliation, regulation of standard work hours, including their limitation, is also essential in this context. Long or excessive work hours interfere with work-life balance (Davaki 2016) and can impede more active assumption of responsibility for the provision of care (Figart and Mutari 2001). Thus, it is in the context of full-time work that changes or modifications are also needed if the goal of encouraging men to shoulder a more equal share of care work and that of enabling women’s access to a broader range of jobs (including full time) are to succeed.

While the relationship between standard work hours and work-family reconciliation has been acknowledged in the CJEU jurisprudence (e.g. SIMAP Case C-303/98 and Jaeger Case C-151/02), the EU’s key instrument regulating standard hours of work – the Directive concerning certain aspects of the organization of working time (2003/88/EC) – does not contain any binding provisions or language that would reflect this. Proposals for inclusion of such provisions (i.e. the right to request variation in work hours) were made by the European Parliament’s Special Rapporteur during the negotiations on the Directive’s revision (from 2004 and 2010) (Recommendation for Second Reading 10597/2/2008, C6—0324/2008, 2004/0209 COD [11 November 2008]; see also ‘Key reading’, Zbyszewska 2016 and ‘Further reading’, Zbyszewska 2016, 118-119). However, those negotiations were ultimately unsuccessful and similar proposals are unlikely to be made within the context of the Working Time Directive in the future, given the European Commission’s recent decision not to reopen that Directive again (see the Commission’s Interpretative Communication on Directive 2003/88/EC (2017/C 165/01)).

As such, the current proposal for an improved right to flexible working arrangements, including reduced working hours, to be available to all working parents of children up to 12 and carers with dependent relatives, which is part of the draft Directive on work-life balance (COM/2017/0253 final, article 9), is a welcome development. What makes this proposed right especially important is the fact that it extends the opportunity to reduce or otherwise vary hours of work also for those workers who are in full time jobs without the need to go part-time, or might enable workers to arrange ‘normal’ hours in a way that is more flexible and adaptable. Thus, the proposal promises to not only widen the range of possibilities for workers seeking flexibility but also to normalize flexible work arrangements, including reduced work hours, in a way that encourage their more equal take up by men.

However, for the right to request to really fulfil its promise and to support also the EU’s gender equality objectives, this right would have to be much more robust than what is currently proposed. For example, the current proposals do not require employers to grant a request, if to do so would interfere with legitimate business considerations. While this sort of balancing is not unusual, if work-family reconciliation policies are to assume a different normative worker – a worker carer – then care responsibilities should not be subordinated to business needs, and adaptability and predictability should be paramount to ensure that rights to request flexibility are in fact workable and effective for those who seek to claim them. For this, significantly stronger language around the employers’ obligation to consider and grant the request would be necessary. Also, the right to request could be accompanied by other related provisions, such as a right to be informed of schedule changes. This, would be especially important for those workers who are in sectors where temporary working-time extensions are customary to the organizational culture and permitted by derogations stemming from the Working Time Directive, or for those workers who have opted out of protective weekly working-time limits or those employed in sectors reliant on on-call work, where opt outs have been widely adopted in many EU member states.

Integration of an extended right to request into the currently proposed Directive on work-life balance is a welcome development, especially as lack of appetite to revise the Working Time Directive means that mainstreaming work-family reconciliation and gender equality objectives therein is unlikely. Making the right to request even more robust than what is currently proposed, however, would not only promote more overall coherence across legal and policy fields by supporting better alignment of working time, work-family reconciliation and gender equality regulations and policy objectives, it would also better facilitate the practical achievement of work-life balance in a way that is consistent with substantive equality goals.

Policy Recommendations

- Strengthen the proposed right to request flexible or reduced work hours (COM(2017) 0253 final, Art. 9) by pairing it with a more robust employer obligation to consider the employee request.

- Consider incorporating rights to be informed of schedule changes and to refuse overtime work in the proposed Directive on work-life balance.

Towards a More Coherent, Sustainable Equality Law and Policy Regime – Our Final

Recommendations

Human dignity and substantive equality are some of the most essential foundational values and objectives of EU equality law (broadly understood). For this reason, they should be mainstreamed into all new EU legislative and policy initiatives, and they should also be considered in revising existing legislation and policies. This is essential to ensure that the inconsistencies that we have identified and discussed in this paper are effectively addressed, and that instrumental objectives do not continue to create internal and systemic incoherencies in the future.

Human dignity and substantive equality are some of the most essential foundational values and objectives of EU equality law (broadly understood). For this reason, they should be mainstreamed into all new EU legislative and policy initiatives, and they should also be considered in revising existing legislation and policies. This is essential to ensure that the inconsistencies that we have identified and discussed in this paper are effectively addressed, and that instrumental objectives do not continue to create internal and systemic incoherencies in the future.

Following the Lisbon Treaty, mainstreaming of anti-discrimination objectives is now envisaged in article 10 TFEU. However, in practice, economic and political considerations often override this principle. To achieve more coherence at the three levels considered in this paper, more weight must be placed on mainstreaming the value of human dignity and the realization of substantive equality, as well as the EU’s and its member states’ international commitments.

Mainstreaming is necessary not only in the negotiation and adoption of legislation, but also in its implementation and interpretation. The inherent constraint of EU legislative and policymaking processes (e.g. requirements of unanimity or qualified majority in the Council) stems from the fact that they rely on political compromises, which can often result in less ambitious laws and minimum standards, legislative instruments that fit ‘awkwardly’ within their policy area or within the whole EU legal system, or legal and policy solutions that prioritize economic over social rights. Thus, member states and (EU and national) courts have a crucial role to play in implementing and interpreting equality-related legislation in a way that preserves the underlying objectives of human dignity and substantive equality, and is aligned with international commitments.

As we have seen from the above case studies, these latter rights are too often subordinated to economic policy objectives and freedoms. In the context of employment, for example, this tends to result in the balance being tilted in favour of employers’ prerogatives and the ‘freedom to conduct a business’. Both, the CJEU’s interpretation of indirect discrimination in Achbita, and the fact that working time/work-life balance legislation still gives employers significant scope to reject employee requests for adaptation of work hours, evidence this prioritization of parties who tend to be in a stronger economic and bargaining position (i.e. the employers). While the ‘freedom to conduct a business’ is a right under article 16 of the EU Charter, this right is not absolute (Case C-281/11 Sky Osterreich) and it has a limited legal basis in the EU treaties (Herresthal 2013; Prassl 2013). Furthermore, unlike the principle of equality (Bell 2011), the right to conduct a business is not considered a general principle of EU law. Accordingly, it should not be used to interpret restrictively other fundamental EU rights and values. EU law and EU institutions should encourage a fairer and more equitable interpretation and balancing of employees’ equality rights and employers’ freedom.

In this regard, the recently proposed Directive on work-life balance (COM/2017/0253 final) strikes a more appropriate balance between employer and employee rights thanks to slightly more expanded right to request working-time adaptation. Its adoption would make-up for the fact that other relevant rights (contained in the Working Time Directive) remain out of scope of work-family reconciliation measures, despite being essential to achieving a better work-family balance, and ultimately, to advancing gender equality goals. As we have noted here, however, there is scope for EU law to be even bolder and to provide for even more robust rights to request.

Another important step towards achieving more coherence, a better balance between social and economic rights, and infusing EU equality law with the objectives of human dignity and substantive equality, would be the adoption of the Horizontal Directive Proposal (COM(2008)0426), which has been in negotiations for nearly ten years. While this new Directive could potentially create new inconsistencies as regards the areas where national equality bodies ought to have powers to operate, extending these powers also to the field of employment (in addition to access to goods and services) would be one way of overcoming them.

These token inconsistencies, and the others that this paper has identified, may indicate that there is a need to review the whole coherence of EU equality law at internal, systemic and external levels. In the aftermath of the launch of the European Pillar of Social Rights, and when almost twenty years of the entry into force of former article 13 EC have passed, it may be a good moment to engage in such a comprehensive review.

Key Reading

Benedi Lahuerta, S. 2016. ‘Taking EU Equality Law to the Next Level: in Search of Coherence’ European Labour Law Journal 3 (Special Issue on Future Directions of EU Labour Law, Jeremias Prassl, ed.).

Zbyszewska, A. 2016. ‘Reshaping EU Working-Time Regulation: Towards a More Sustainable Regime’ European Labour Law Journal 3 (Special Issue: Future Directions of EU Labour Law, Jeremias Prassl (ed.)).

Further Reading

Benedi Lahuerta, S. 2016. ‘Ethnic discrimination, discrimination by association and the Roma community: CHEZ’, Common Market Law Review 53.

Benedi Lahuerta, S. 2013. ‘Untangling the application of the EU equality directives at national level: a bottom-up approach’, CELLS Online Paper Series.

Benedi Lahuerta, S. 2012. ‘Regulating the use of full face covering veil: which model should Spain adopt?’, Revista General de Derecho Canonico y Derecho Eclesiastico del Estado 28, ISSN-e 1696-9669.

Benedi Lahuerta, S. 2009. ‘Race equality and TCNs, or, how to fight discrimination with a discriminatory law’ 15(6) European Law Journal 738.

Zbyszewska, A. 2016. Gendering European Working Time Regimes: The Working Time Directive and the Case of Poland (Cambridge: CUP).

Zbyszewska, A. 2013. ‘The European Working Time Directive: Keeping the Long Hours with Gendered Consequences.’ 39(1) Women’s Studies International Forum 30 (Special Issue: The Unintended Gender Consequences of EU Policy, Jill Attwood and Heather McRae (eds.)).

Zbyszewska, A. 2012. Regulating working time in the times of crisis: flexibility, gender and the case of long hours in Poland. 28(4) International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 421.

Zbyszewska, A., and Kresal, B. 2017. ‘Through Work-Life-Family Reconciliation to Gender Equality? Slovenia and the United Kingdom’s Legal Frameworks Compared’ in Bulletin of Comparative Labour Relations (on Work Life Balance) vol 98.

References

Bell, M. 2011. ‘The Principle of Equal Treatment: Widening and Deepening’ in P Craig and G de Búrca (eds), The Evolution of EU Law (OUP 2011) 611.

Daviaki, K. 2016. Differences in men’s and women’s work, care and leisure time. Study for the European Parliament’s Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality. 2016, available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/supporting-analyses-search.html.

EU Parliament, 2013. Report on the EU Roadmap against homophobia and discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity (2013/2183(INI)) – A7-0009/2014).

European Commission, 2017. Report on equality between women and men in the European Union, 2017 available at https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/72e1386a-40f4-11e7-a9b0-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

Eurobarometer, Discrimination in the EU in 2015, Report 243, available at http://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/SPECIAL/surveyKy/2077.

Fagan, C., Lyonette, C., Smith, M., and Saldana-Tejeda, A. 2011. The Influence of Working Time Arrangements on Work life Integration or ‘Balance’: A Review of the International Evidence, (Geneva: ILO).

Figart, E. and Mutari, E. 2001. ‘Europe at a Crossroads: Harmonization, Liberalization, and the Gender of Work Time’ 8(1) Social Politics 53.

Garner, S. and Selod, S. 2015. ‘The racialization of Muslims: empirical studies of Islamophobia’ 41 Critical Sociology 9.

Herresthal, C. 2013. ‘Constitutionalisation of Freedom of Contract in European Union Law’ in K Ziegler and P Huber (eds), Current Problems in the Protection of Human Rights (Hart).

Miller, W. 2009. ‘Beguiled By Metaphors: The “Living Tree” and Originalist Constitutional Interpretation in Canada’ 22 Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence 331.

Müller-Uri, F. and Opratko, B. 2016. ‘Islamophobia as Anti-Muslim Racism: Racism without “Races”, Racism without Racists’ 3 Islamophobia Studies Journal 116.

Prassl, J. 2013. ‘Transfers of Undertakings and the Protection of Employer Rights in EU Labour Law’ 42 Industrial Law Journal 434.

Sheppard, C. 2001. ‘Grounds of Discrimination: Towards an Inclusive and Contextual Approach’ 80 Canadian Bar Review 893.